A Corruption Watch investigation has revealed that some key governance institutions, which should promote access to information, are either refusing or failing to comply with the Right to Information (RTI) law by denying access to information requested by citizens.

This refusal or failure to provide the requested information has led to the imposition of fines by the RTI Commission (RTIC).

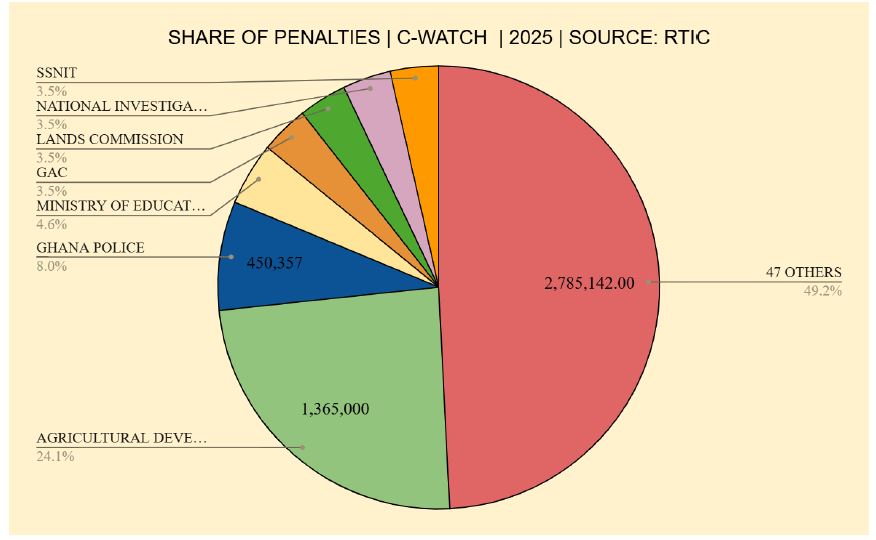

The records show that as of 16th July 2025, the RTIC had imposed penalties of approximately 5.6 million cedis in 76 determinations involving 64 separate institutions.

So far, 23 erring institutions have paid approximately 3.5 million cedis as penalties to the RTIC for breaking the law.

Yet, a further 36 separate institutions owe the RTIC a combined total amount of GHS2,149,000 in unpaid penalties.

The figure is exclusive of interests that have accrued on some of the fines that have been imposed.

In addition, the value of penalties does not include those that are being litigated in court.

Genevieve Shirley Lartey, Esq., Executive Secretary of the RTIC stresses that the fines imposed do not serve as a substitute for the information that is supposed to be released to an applicant.

“…a fine is never a substitute for information being requested…Once you are compelled to pay the administrative penalty, it does not automatically erase the fact that you have to provide the information… So, the penalty we will collect all right, and then we will ensure that you provide the information being requested.”

Background

Protests, marches, debates, fallouts, and harassments characterised more than 20 years of activism and advocacy to demand a right to information law in Ghana.

It is more than five years since the implementation of the Right to Information (RTI) law began. The purpose was to make access to information easier.

The RTI Act was passed in March 2019 to empower citizens to access information from public and private institutions that provide public services, enhance transparency and accountability, and stimulate the fight against corruption.

The passage of the RTI law also gave meaning to Article 21[1(f)] of the 1992 Constitution, which provides that “All persons shall have the right to information, subject to such qualifications and laws as are necessary in a democratic society.”

The RTI law is beneficial to citizens because it allows them to demand information about happenings around them that impact their lives. Under the RTI law, a person may request information from a state or a qualifying private institution by writing a letter addressed to the Information Officer of the institution.

The Information Officer is to provide the information within 14 days if the information is not exempt. If the Information Officer does not provide the information within 14 days, then the requester can appeal to the head of the institution, which gives the head of the institution 15 days to provide the information.

If the head of the institution does not provide the information, then the requester can file a complaint with the RTIC or the High Court.

Violators

Meanwhile, the list of violators of the law is long and includes oversight bodies such as the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ), which is yet to pay a fine of GHS30,000, the Judicial Service of Ghana, also yet to pay a fine of GHS100,000, the Attorney-General’s Department, also yet to pay a fine of GHS50,000, the Public Procurement Authority (PPA), yet to pay a fine of GHS100,000, the Ghana Police Service, which has paid GHS450,357, the Ghana Audit Service, which has paid GHS60,000, and the Parliamentary Service, which has paid GHS53,785.

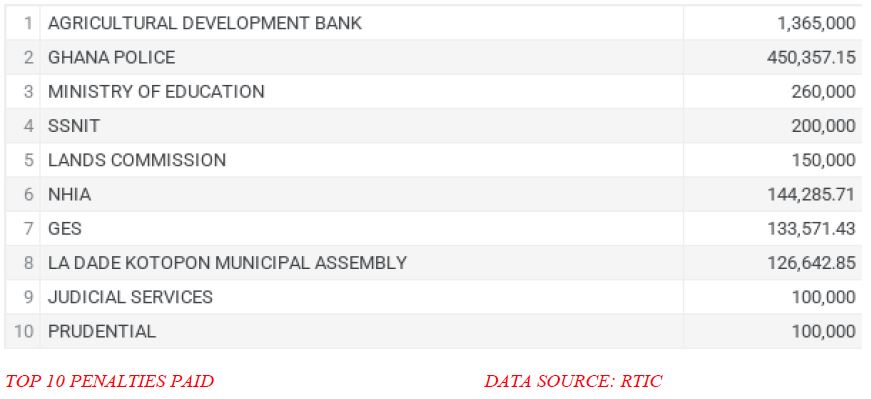

Five institutions have paid the heaviest fines. They are the Agricultural Development Bank ( GHS1.365 million), Ghana Police Service (GHS450,357), the Ministry of Education (GHS260,000), the Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) – GHS200,000, and the Lands Commission (GHS150,000).

In terms of frequency, the Ministry of Education ranks highest with four penalties received, while the Ghana Police Service has received three penalties. Ten other institutions have suffered two penalties each. They include the Ghana Education Service (GES), the Judicial Service, the Lands Commission, the PPA, the Ministry of Energy, and the Urban Roads Department.

What is worse, state institutions have been using taxpayers’ funds to pay for fines imposed on them by the RTIC.

Zakaria Tanko Musah, a private legal practitioner, opines that using state funds to settle the fines has little impact on the person who willfully refused to provide the information to the requester.

“…if you fine an institution, that money is not going to come from the person who willfully refused to provide you with the information, although he or she knows that the information is supposed to be provided. The money is going to be paid by the institution, so they don’t suffer any damage; they don’t suffer any embarrassment, per se.”

Further checks by Corruption Watch have revealed that the Agricultural Development Bank, despite paying the GHS1.365 million) fine imposed on it, is in court contesting the amount.

Previously, the Ghana Police Service had been in the courts to litigate various fines imposed on it, but eventually the leadership of the Service discontinued the litigations and settled fines worth 450,357 cedis.

Corruption Watch has further learned that the GCB Bank, in which the State has shares, as well as the private mobile telecommunication operator, Scancom Ghana Limited, are also in the courts to contest fines imposed by the RTIC.

Prudential Bank, which has been slapped with a fine of GHS100,000, is the only private institution to have settled a fine.

Other notable institutions slapped with heavy fines are the Ghana Airport Company Limited (GACL), GHS200,000; the National Intelligence Bureau (NIB), GHS200,000; the National

Health Insurance Authority (NHIA), approximately GHS144,000; the GES, approximately GHS134,000; GOIL, GHS100,000; and the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA), GHS20,000.

At the municipal level, the La Dade Kotopon Municipal Assembly paid GHS 126,642.85, East Mamprusi Municipal Assembly paid GHS 27,857.14, and Keta Municipal Assembly paid GHS 5,000 out of fines worth 40,000.

Therefore, it still owes the RTIC a total of 35,000. Other assemblies that owe monies to the RTIC are Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA) – GHS50,000, Ledzokuku Municipal Assembly (GHS29,000, while each of Aowin Municipal Assembly, Asokore Mampong Municipal Assembly, Bosom Freho District Assembly, and Saboba District Assembly owes GHS20,000.

The irony of the fines is that while they serve as internally generated funds for the RTIC, they amount to a cost for the institutions that are paying them.

The overwhelming majority of institutions that have paid fines are state institutions, highlighting a major issue of non-compliance.

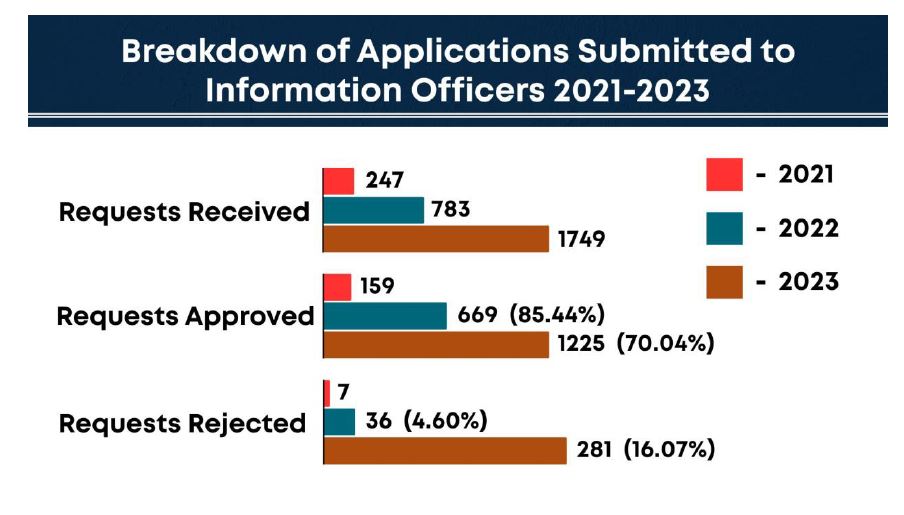

Statistics obtained and analyzed by Corruption Watch during this investigation show that compliance with the law weakened between 2022 and 2023, after having improved the previous year.

Despite this, Shirley Lartey, Executive Secretary of the RTIC, says their monitoring of about 700 institutions shows that compliance with the Act has been improving.

“Over the period, we have monitored about 728 institutions between 2022 and 2024. Out of the 728, we have 489 compliant institutions and 239 non-compliant institutions. So, I can say that it’s been gradually improving with increased awareness over the years…”

However, Corruption Watch analysis of data contained in the annual reports of the RTIC for the period 2020 to 2023 shows that the approval rate for RTI requests by RTI officers slumped by 15 percent between 2022 and 2023.

Data for 2024 is not yet accessible to the public because, at the time of filing this report, the 2024 annual report of the RTIC was still under review.

According to the annual reports of the RTIC, information officers of public institutions approved 85.44 percent of requests that they received in 2022 whereas they approved only 70.04 percent of requests they received in 2023. On the other hand, the rejection rate jumped from 4.60 percent in 2022 to 16.07 percent in 2023.

The annual reports further indicate that dismissal of review applications submitted to heads of institutions increased sharply from 17 percent in 2022 to 43 percent in 2023.

Reactions

Considering the number of institutions that have received fines, Corruption Watch opted to sample reactions from some of the institutions about the impact of the fines imposed on them.

Thus, Corruption Watch wrote to request separate interviews with the Agricultural Development Bank, which paid the highest sum as fine, Ghana Police Service, the Lands Commission, the Ghana Audit Service, the State Housing Company (SHC), and the NHIA.

In a terse letter dated 14th May 2025, the Agricultural Development Bank responded to Corruption Watch that “…the matter is currently the subject of a court suit pending at the High Court, Accra, and as such, we are unable to publicly comment on the same at this time.”

On its part, the Lands Commission did not proceed with an interview after Corruption Watch turned down its request to have us sign an “undertaking agreement” as a condition for the interview. The said undertaking was seeking, among other things, to review our content before publication.

We could not schedule an interview with the Ghana Police Service at all while the NHIA did not respond to our request.

Only the Ghana Audit Service and the State Housing Company granted our requests for interviews.

In the case of the Ghana Audit Service, it found itself in a fix when it was slapped with the GHS60,000 fine.

The oddity about its case is that it is the only institution that paid the fine in cash in an era where the government is insisting on electronic transactions.

According to Frederick Lokko, Assistant Director of Audit, who doubles as Information Officer, the Audit Service had to negotiate with the RTIC on the mode of payment. Eventually, the Service paid the penalty in cash to the Commission.

Unlike the Audit Service, the SHC did not readily have funds to settle its GHS50,000 fine in one instalment. Margaret Zokli, Administrative Manager at the company, disclosed that a team from the company negotiated with the RTIC to allow them to pay the fine in installments.

Reforms

Among the gaps identified during this investigation are the absence of a legislative instrument (LI) to provide more granular details for the implementation of the RTI Act. Another is the inadequate transparency of the criteria for determining the amount to impose as fines.

Touching on the transparency of the criteria for determining the amount to impose as fines, Ms Mina Mensah, Director of the Africa Office of the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI), said “I don’t think there’s a lot of transparency. I don’t think people really know the criteria they use.

That might be because of the fact that the LI is not ready. Maybe the LI will stipulate all these things. Of course, anecdotal information that I have suggests that it’s normally based on people’s ability to pay…There are international standards, international best practices that they should go through, but then I do not know whether they use that.”

She added that “without the LI, for instance, there are no standards as to what information is supposed to be proactively disclosed. There are no standards. So, this institution might want to proactively disclose this. That institution might want to proactively disclose that. But with an LI, at least some standards will come out, and then they should be able to do that. So I think we should encourage more proactive disclosure. More proactive disclosure would be useful in getting citizens to engage with the law. And it makes it easier.”

According to Musah, there should be a consideration of a surcharge against institutional heads whose actions lead to RTI fines.

“If he were willful, negligent, or reckless, then we may have to start considering surcharging that individual. And, how do we do the surcharge? That individual is in the workplace, and he earns a salary. His salary should be attached.”

Lokko of the Audit Service supports this call. “…when it comes to the payment of fines, for example, my personal view is that…there would be prescribed sanctions, administrative sanctions, that probably can be brought to bear on either the spending officer or head of institution, or head of finance, whoever.”

Shirley Lartey, Executive Secretary, says that the RTIC plans to increase its sensitization drive across the country by expanding its geographical footprint.

“So, you would realize that…we have presence in Bono, we have presence in Ashanti Region. And we have presence also in Bolga [Upper East Region]. And this year, our mandate is to go into five additional regions in Cape Coast [Central Region], Eastern Region, Volta [Region], Takoradi [Western Region], and Tamale [Northern Region]. So, the drive is to reach out to people in the hinterlands, to reach out and sensitize the Ghanaian on their rights and access to information.”

In conclusion, the executive secretary said, “We realize that in every law there are gaps. That is why we have an LI tabled that would try and fill in all the gaps that the current act provides. So once all these things are dealt with, we believe that we will have a strong working tool going forward.”

By Frederick ASIAMAH, Investigative Journalist, Corruption Watch