Once upon a time in the Republic of Uncommon Sense, there was a groom whose wedding was the talk of the town. The whole village gathered to dance, to eat, and to drink in his joy.

He wore his kente proudly, the drummers beat their atumpan until midnight, and the praise-singers composed ballads in his name. The honeymoon feast overflowed with jollof and fufu, and every guest left declaring, “This groom shall surely prosper.”

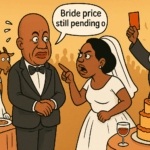

But as the elders say, “The sweetness of the soup is known only after the second day.” Today, that same groom is being whispered about in corners. The food has finished, the bride price is still unpaid, and the same guests who clapped are now gossiping. This, dear reader, is how President Mahama’s approval ratings have slid from honeymoon heights to the slippery slope of public disappointment.

Pollsters, those modern-day marriage counsellors, now chart his popularity like a couple’s marriage satisfaction survey. From 70% in the early days — when the soup was still hot and spicy — to 45% today, when the meat has sunk to the bottom of the pot. Citizens wonder if the marriage vows are already fraying.

The scandals have not helped. The appointments purge was like a groom bursting into his own wedding kitchen to sack every cook hired after 7 December. Pots overturned, aprons seized, and the stew half-cooked. Those dismissed cooks still linger at the gate, holding their ladles, wondering if they should reapply as guests.

Then came the ghost names saga — 81,000 phantom guests who allegedly collected allowances from the National Service pot. Imagine a wedding where invisible guests are eating from the soup while the living chew dry cassava. Laughter and curses mingled: some joked that these ghosts might as well register to vote; others whispered that they had already been appointed head cooks.

And as if the comedy of ghosts was not enough, the drama of the Chief Justice stormed the stage. Madam Gertrude Torkornoo, referee of the national match, suddenly found herself shown a red card in her own game. First, she was suspended, then formally removed — like a judge who becomes the accused in the very court she presides over. In Uncommon Sense fashion, the people asked: if even the referee is chased from the field, who will blow the whistle when the strikers foul?

But perhaps the biggest disillusionment of all is the President’s seemingly indecisive war on galamsey. Once, he was the fiery suitor promising to chase illegal miners from the bride’s backyard. Today, the rivers are brown, the cocoa farms are craters, and the miners still dance freely on sacred stools. In the Republic of Uncommon Sense, fighting galamsey has become like chasing a goat with a Bible — plenty of words, little capture. The people sigh: if a groom cannot even guard his own kitchen garden, how will the marriage prosper?

And just when the bride thought it could not get worse came the whispers of loot and looters. Stolen goods from yesterday’s feast still sit on the high table, untouched, while hungry guests wait. Prosecution has been delayed, and some government insiders themselves mutter — like Fiifi Kwetey — that deals are being cut with suspected looters. In this marriage, the stolen dowry has not been returned, and the bride wonders if her groom is secretly bargaining with the thieves under the table.

Civil society, that noisy neighbour across the fence, has joined in. IMANI, the professional matchmaker, now announces that “the honeymoon is over.” Opposition leaders sit under the big tree, arms folded, saying smugly, “Did we not warn you?” Meanwhile, the ordinary Ghanaian — the bride in this marriage — is left holding a leaking bucket of expectations.

International observers are no less amused. The IMF, World Bank, and Fitch — the foreign guests at the wedding — have started asking for receipts for the drinks they donated. They came expecting champagne but were served sachet water. Their smiles have grown thin.

But the sharpest sting comes from within. Teachers, taxi drivers, and nurses — the guests who never got food at the wedding — now find themselves paying the bills. They danced that night, but their stomachs are still waiting.

And so the President’s approval ratings slide like oily waakye on a polythene bag — slippery, staining trousers, impossible to package neatly. The more his handlers try to hold onto it, the faster it glides downhill.

Yet satire is mercy wrapped in laughter. We must recall the proverb: “When the yam seller loses weight, it is not because he ate his own yam.” President Mahama’s weight loss in approval ratings is not personal — it is the economy, the ghost names, the purges, the galamsey indecision, the delayed loot recovery, and the courtroom drama that have gnawed away at him.

Approval ratings, like kelewele, are sweet when hot. But once the pepper burns your throat, you scramble for water.

So let us end with a benediction from the Republic of Uncommon Sense: May the bride price be paid in full, may the soup be stirred again, and may our leaders’ honeymoons last longer than a sachet of groundnut paste.