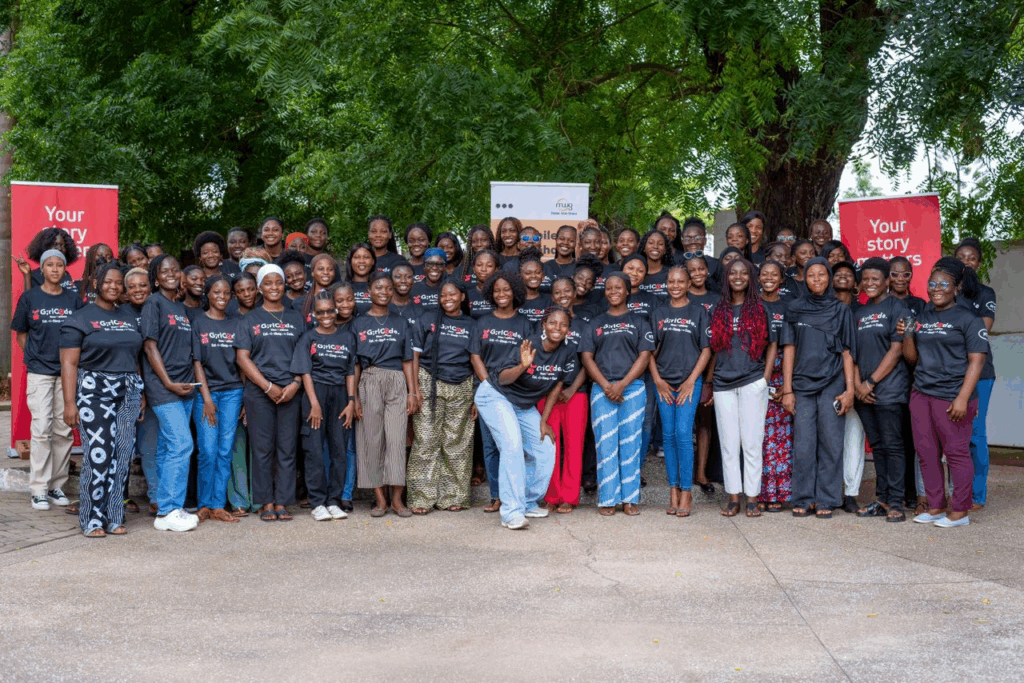

Last month in Accra, 100 young women gathered for a 30-hour coding challenge. I watched in fascination as scribbled notes, strings of code, and lively conversations turned into innovative technology solutions. What stayed with me, however, was not only the ideas that emerged from the event, but the confidence of the participants. For many of these girls, this event, the GirlCodeHack 2025, was their first step into an industry that has been traditionally dominated by men.

GirlCodeHack is now in its eleventh year. In 2025, the partnership between Absa and GirlCode expanded from three to five countries and ran simultaneously across eight African cities: Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban, Accra, Nairobi, Kampala, Dar es Salaam, and Gaborone. The brief was ambitious, and rightly so: “Future-Proofing Africa: Innovation at the Intersection of FinTech, Cybersecurity, and AI.”

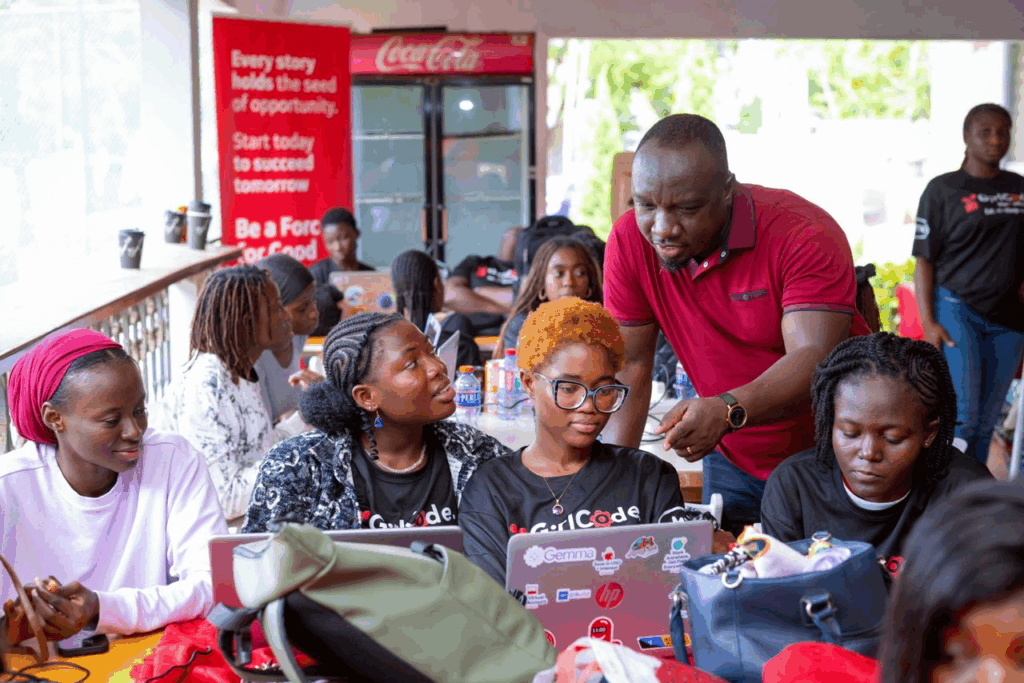

Over two days, teams of two to four participants set out to identify real problems and build practical solutions. As a technology leader, however, I am always concerned about what happens after the laptops close: a hackathon is not an end; it should be a starting line. The young women I met were not simply writing code; they were testing teamwork, leadership, and judgment under tight deadlines. These are the habits that employers look for and that founders need when the novelty of a new idea wears off and the work of building begins.

For Absa Bank, supporting GirlCodeHack is part of a deliberate approach to education, entrepreneurship, and employability within our Force for Good agenda. It sits alongside initiatives like ReadytoWork, which provides young people with structured learning on work skills, people skills, money skills, and entrepreneurship, with additional content on digital literacy, project management, the gig economy, blockchain concepts, and computational thinking. These initiatives create a pathway for young people to learn the fundamentals, apply them in real settings, and take the next step into work or enterprise.

Two brief encounters at the Accra event cemented the importance of this approach for me. One participant, Aduboahemaa, said she became interested in ICT from class three through junior high. For her, tools such as Scratch and Excel opened the door to bigger questions about technology. At the hackathon, she chose her team carefully, looking for alignment around artificial intelligence in education rather than the more popular streams of FinTech or cybersecurity. For another girl, Talia, the route was different. She discovered ICT in secondary school, recognised she had a natural aptitude, and entered the hackathon on the encouragement of a former student association president. Both spoke about the confidence they gained from participating in GirlCodeHack. The word ‘confidence’ is the bridge between potential and performance. However, for that confidence to be sustained for many more young women, several things must happen.

First, there must be structured follow-through. Innovation must not end with the final pitch. Teams need practical next steps. Each should leave with a simple but actionable roadmap: a clear problem statement, a defined pilot scope, a user testing plan, and a list of partnerships or resources required for further development. Without this structure, even the best ideas risk stalling at the prototype stage.

Second, they need practical exposure. Technical skills flourish in real-world environments. If we want to bridge the gap between classroom knowledge and employability, participants must be given opportunities for hands-on learning through internships, mentorships, or project briefs inside real organisations. At this year’s event, I was heartened to see that the top two teams in Accra earned internship opportunities with AmaliTech, an IT service company based in Germany, the US, Ghana, and Rwanda. Such opportunities offer young people the right bridge between learning and work.

Third, hackathons should be linked to broader learning journeys that reinforce both technical and soft skills. For example, Absa Bank’s ReadytoWork platform provides foundational technology modules. More young women should be encouraged to complete these modules and advanced digital tracks, then return to build-spaces like GirlCodeHack with not just technical knowledge but the discipline and collaborative spirit that drive results.

There is also a responsibility on the industry. Employers should look beyond narrow job specifications and widen entry routes. Apprenticeships, project residencies, mentorships, and outcome-based assessments give capable candidates the space to prove themselves. The benefit is mutual: organisations gain motivated contributors and a more diverse problem-solving culture, while participants gain experience that compounds over time.

The lesson from GirlCodeHack this year is not just that we hosted a successful event. It is that there is a cohort of young women ready to build, if we keep the door open and the path clear. The energy in that room will fade if it is not met with a practical opportunity. Our task, as employers, educators, and partners, is to create those opportunities. That is how Ghana can strengthen its technology talent base, and how more young women can move from learning to earning with confidence.

******

The writer, Justice Amegashie, is the Chief Information and Enablement Officer of Absa Bank Ghana Limited