The year was 1965.

On a Sunday in Jaunti, a small village on Delhi’s outskirts, a hardened Indian farmer stretched out his hand to a visiting farm scientist.

“Dr sahib, we will take up your seed,” he said.

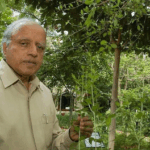

The scientist was MS Swaminathan – later hailed by Time magazine as “the Godfather of the Green Revolution” and ranked alongside Gandhi and Tagore among India’s most influential figures of the 20th Century.

When Swaminathan asked what had convinced the farmer to try his experimental high-yield wheat that day, the man replied that anyone who spent his Sundays walking from field to field for his work was driven by principle, not profit – and that was enough to earn his trust.

The farmer’s faith would change India’s destiny. As Priyambada Jayakumar’s new biography, The Man Who Fed India, shows, Swaminathan’s life reads like the story of a nation’s leap from “ship-to-mouth” survival to food self-sufficiency – reshaping not just India, but Asia’s approach to food security.

Years of colonial policies had left Indian agriculture stagnant, yields low, soils depleted, and millions of farmers landless or in debt. By the mid-1960s, the average Indian survived on just 417g of food a day, reliant on erratic US wheat imports – a daily wait for grain ships became a national trauma.

So dire was the shortage that the then-Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru urged citizens to substitute wheat with sweet potatoes, while the nation’s staple carb, rice, remained critically scarce.

The ‘Green Revolution’ turned parched fields into golden harvests, doubling wheat yields in just a few years and transforming a nation on the brink of famine into one of Asia’s food powerhouses. It was science in the service of survival, and Swaminathan led the way.

Born in 1925 in Kumbakonam, Tamil Nadu, Swaminathan grew up in a family of landlord farmers who prized education and service. He was expected to study medicine, but the 1943 Bengal Famine, which killed more than three million people, stirred him.

“I decided to become a scientist to breed ‘smarter’ crops which could give us more food… If medicine can save a few lives, agriculture can save millions,” he told his biographer.

So he pursued plant genetics, earning his PhD at Cambridge and then working in the Netherlands and at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines. In Mexico, he met Norman Borlaug, the American agronomist and Nobel Prize winner, whose high-yielding dwarf wheat variety would become the backbone of the ‘Green Revolution’.

In 1963, Swaminathan persuaded Borlaug to send Mexican wheat strains to India.

Three years later, as part of a nationwide experiment, India imported 18,000 tonnes of these seeds. Swaminathan adapted and multiplied them under Indian conditions, producing golden-hued varieties that yielded two to three times more than local wheat while resisting disease and pests.

The seed import and rollout was far from smooth, Jayakumar writes.

Bureaucrats feared dependence on foreign germplasm, logistics slowed down shipping and customs, and farmers clung to tall, familiar varieties.

Swaminathan overcame these challenges with data and advocacy – and by personally walking the fields with his family, offering seeds directly to farmers. In Punjab, he even enlisted prisoners to stitch seed packets for rapid distribution during the sowing season.

While the Mexican short-grain wheat was red, Swaminathan ensured the hybrid varieties were golden to suit leavened Indian breads like naans and rotis. Named Kalyan Sona and Sonalika – “sona” means gold in Hindi – these high-yielding grains helped turn the northern states of Punjab and Haryana into breadbaskets.

With Swaminathan’s experiments, India quickly shifted to self-sufficiency. By 1971, yields had doubled, turning famine into surplus in just four years – a miracle that saved a generation.

Swaminathan’s guiding philosophy was “farmer-first”, according to Jayakumar.

“Do you know the field is also a laboratory? And that farmers are actual scientists? They know far more than even I do,” he told his biographer.

Scientists, he insisted, must listen before prescribing solutions. He spent weekends in villages, asking about soil moisture, seed prices, and pests.

In Odisha, he worked with tribal women to improve rice varieties. In the dry belts of Tamil Nadu, he promoted salt-tolerant crops. And in Punjab, he told sceptical landowners that science alone wouldn’t end hunger and that “science must walk with compassion”.

Swaminathan was keenly aware of the challenges facing Indian farming. As chair of the National Commission on Farmers, he oversaw five reports between 2004 and 2006, culminating in a final report that examined the roots of farmer distress and rising suicides, calling for a comprehensive national farmers’ policy.

Even in his late 90s, he stood with farmers – at 98, he publicly supported those protesting in Punjab and Haryana against controversial agricultural reforms.

Swaminathan’s influence extended far beyond India.

As thefirst Indian Director-General of the IRRI in the Philippines in the 1980s, he spread high-yield rice across Southeast Asia, boosting production in Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

From Malaysia to Iran, Egypt to Tanzania, he advised governments, helped rebuild Cambodia’s rice gene bank, trained North Korean women farmers, aided African agronomists during the Ethiopian drought, and mentored generations across Asia – his work also shaped China’s hybrid-rice programme and sparked Africa’s Green Revolution.

In 1987, he became the first recipient of the World Food Prize, honoured as a “living legend” by the UN Secretary-General for his role in ending hunger.

His later work through the MS Swaminathan Research Foundation in Chennai focused on biodiversity, coastal restoration and what he called a “pro-poor, pro-women, pro-nature” model of development.

The Green Revolution’s success also brought serious costs: intensive farming drained groundwater, degraded soil and contaminated fields with pesticides, while wheat and rice monocultures eroded biodiversity and heightened climate vulnerability, especially in Punjab and Haryana.

Swaminathan acknowledged these risks and, in the 1990s, called for an “Evergreen Revolution” – high productivity without ecological harm. He warned that future progress would rely not on fertiliser, but on conserving water, soil, and seeds.

A rare public figure, he paired data with empathy – donating much of his 1971 Ramon Magsaysay Award amount to rural scholarships and later promoting gender equality and digital literacy for farmers long before “agri-tech” was a buzzword.

Reflecting on his impact, Naveen Patnaik, former chief minister of Odisha, says: “His legacy reminds us that freedom from hunger is the greatest freedom of all.”

In Swaminathan’s life, science and compassion combined to give millions that very freedom. He died in 2023, aged 98, leaving a lasting legacy in sustainable, farmer-focused agriculture.