Where even silence was a language, and every proverb a map

PART I: The Voice Before the Light

In the time before alphabets and foreign flags, when the earth still hummed with the pulse of ancestral drums, there existed the Kingdom of Nunyãdume, a kingdom not ruled by kings or warriors, but governed by the breath of the ancestors and the rhythm of the community that bridged between their thoughts. The people of Nunyãdume honoured this truth. Their ancestors carved their knowledge not into stone tablets, but into drums, stories, and names. The child was named not for fun, but for prophecy. The proverb was not for wit, but for wisdom coded in rhythm.

In the beginning, even before the rivers knew their beds, there was only chaos and great silence before the baobab bore witness to time. Darkness clothed the deep, and all was formless. The stars were still unborn, and the wind whispered no name. But then, from the bosom of the East, where the sun takes its first breath each morning, came not thunder, nor fire, but a Voice.

The Elders of Nunyãdume said that when the Creator prepared to awaken the world, He did not first summon light or craft man from clay. No. The first gift was Word.

“And God said…,” and with that speech, light burst forth and clothed the sky. From Word came Light, and from Light came Life. Even now, sunlight remains the ultimate source from which all energy in our galaxy flows.

Thus, it was known in Nunyãdume that language is not merely a foundational tool of human communication, but also a vessel for cultural expression and a spark for cognitive development.

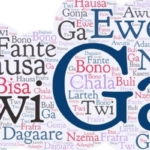

To hear the rise and fall of tone in Ga, even if it appears confrontational. The softness of Fante vowels. The protest in Dagbani idioms. The rootedness of the Ewe proverbs. Each language carved the mind in different shapes, some curved in communal metaphors, others sharp with logic.

To name is to know. To speak is to call into being.

Language is the soul’s drum; when silenced, a nation forgets how to dance.

PART II: The Silence that Followed the Scrolls

Yet in the age of digital scrolls and borrowed alphabets, the people of Nunyãdume began to forget. They forgot the very tongues with which Mother Africa first suckled them, and the ancestral languages were now fading like the footprints of spirits on the harmattan soil. In their music, on their radios, and even in the preschools, where minds should be moulded in the clarity of their mother tongue, they code-mix, thinking it fashionable. They are made to believe that blending foreign tongues with their own is a sign of progress, when it is the quiet erosion of identity.

Children now learned to read in tongues their mothers never spoke. Judges gave verdicts in foreign codes. And healers prescribed remedies in accents their patients feared. In time, the people no longer wept in their language. They wailed in another man’s vocabulary.

The elders called this “cutting one’s own tongue to chew another’s meat.” For the very knowledge that once lived in the market songs, birthing chants, and ancestral praise poems was now smothered in silence. “When the drum speaks in another tongue, even the dancer stumbles,” the drummers lamented. “A parrot may mimic English,” an elder said, “but it is not the same as understanding the forest.”

A strange affliction spread, one unseen, yet heavy like harmattan dust. Soon, the children of Nunyãdume could list the planets, yet not describe the moon in their mother’s tongue. They could spell “metamorphosis,” but not recount how the tortoise outwitted the leopard. The young could spell “photosynthesis” but not name ten trees in their grandmother’s farm.

Their sacred names became “middle names.” Their stories became “folklore.” Their tongues became “local dialects”, as though to speak one’s truth was to be small.

They had grammar but no grounding, vocabulary but no vision. The nation had speech, but no voice.

PART III: The Council Beneath the Baobab

The Seer of Nunyãdume, Nanagah Nyekokpi, the Wise, convened the Linguistic Council beneath the Baobab of Memory. There, she unrolled the scrolls of distant sages and spoke of Whorf of the North, who taught that the language one speaks does not merely reflect thought, but shapes it. “If your tongue lacks a word,” Whorf argued, “your mind may lack the concept.” Like those who have no names for Red, Wine, and Burgundy, are their eyes blind to the subtle differences, or their minds untrained to notice them?

“You say we lack a word for cousin,” she said. “But the absence of a word does not mean the absence of thought. Among the Ewe, your Wofa is your mother’s brother, and your father’s brother is Togah or Toda, depending on whether he is older or younger than your father. Your mother’s sister is Nogah or Noda, and your father’s sister is Tasi. These are not generic ‘aunts’ and ‘uncles,’ but specific titles wrapped in inheritance, duty, and kinship. Even if the Wofa is a twin, tribal nuance applies: the younger twin, who in English would be called the ‘first twin’, becomes Wofakumah, and the younger paternal twin sister becomes Tasikuma”

The children sat straighter.

“And what of cousins?” they asked. “Among the Akans, there is no need for such a word, because your cousin is your sibling. In a matrilineal world, your father’s sister’s child is your co-heir, blood, and continuity. To call them otherwise, to distance them by English convenience, is seen not as precision, but as betrayal.”

She paused. “So, you see, it is not that we do not think it, we think it differently. And difference, my children, is not deficiency.”

“And so,” she said, “when a people abandon their mother tongue, they do not merely lose words, they misplace their mother’s wisdom.”

Nanagah Nyekokpo spoke of Broca, Wernicke, and the arcuate fasciculi, but the people only nodded when she turned to the sacred stories of Ananse, and to the mystery of a single word: “la.”

“In Ga,” she said, “la can mean fire, or blood, or tongue, or to sing, and it is even the name of a place.”

She paused, letting the word roll through the air like a drumbeat.

“With one tone, it burns. With another, it bleeds. In one breath, it speaks. In another, it sings. And in another, it becomes a place where memory sleeps.”

She looked up. “You see? It is not just grammar.

It is thunder made tender, and silence made sacred.”

PART IV: The Return of the Drumbeat

The scholars had argued for years. They knew from science that multilingualism sharpened the mind like a blacksmith’s knife. They knew from research that mother-tongue education made minds bloom faster than foreign tongues. But in the corridors of power, English was still the only key that unlocked doors.

The classrooms, like courtrooms and consulting rooms, had become altars of exclusion.

As one elder wept, “Our children are being schooled into forgetfulness. Their brains are sharp, but their roots are bare.”

From Wulensi to Winneba, elders began to tell the tale of “The Orphan Word”, a parable of a child born mute because his mother was told her language was worthless. But when a grandmother began to hum the old lullabies, the child began to speak, not in English, but in truth.

In that tale, language was not taught; it was remembered. Like a spirit, it was summoned through rhythm, context, and love.

A boy once asked his teacher, “Why do I feel stupid in school but clever at home?” The teacher wept, for he had asked the question of a generation.

One of the scribes of the Seer, a healer of minds and hearts, once shared a tale of a boy from the eastern hills, brought to the city to “catch up” with learning. The boy was nine, quiet, and always behind in school. His uncle, a teacher, complained bitterly: “Even my younger children are ahead, this one cannot follow even the simplest lesson.”

But the healer did not ask the boy to spell “Transmogrification” or “Chrysopoeia”, words dressed in cloaks his soul had never worn. Instead, he asked a simple question: “How do you prepare palmnut soup?” And the boy, in the river-song rhythm of Twi, and like a flood bursting through a dam, described the process with exactitude and confidence, from boiling the nuts to sieving the pulp, from the seasoning to the slow boil that releases the aroma. His uncle, who was a man of books, listened, astonished, for he did not know half of what the boy said. The wisdom had always been there; it only needed to be asked in the language of home.

The healer turned to him, saying, “Your nephew does not lack thought, only translation. His mind is a river; the problem is your pipe. Tilapia or Koobi, depending on what process it has gone through, does not fail in school because it could not climb Mount Afadja from the depths of the Volta River. It swims where it was made to thrive. The question is not whether he can learn, but whether the lesson speaks his language.”

The philosophers of Nunyãdume said, “A nation that clothes its laws in a stranger’s tongue may one day not recognise its own reflection.”

PART V: Reclaiming Voice, Restoring Vision: The Rise of Linguistic Justice in Nunyãdume

When misinterpretations at hospitals led to needless deaths, when court rulings punished the innocent because meaning got lost in translation, when students dropped out, not for lack of brain, but because the lesson came in a tongue their heart didn’t trust, then the people began to murmur.

And those murmurs became a movement.

The Council of Drummers, the Custodians of Proverbs, the Neuroscribes, and the Griots of the Silent Age came together. They did not ban English—they braided it. With Ewe. With Dagbani. With Twi. With Gonja. For they knew, “The beauty of a cloth is in the mix of its threads.”

They crafted a new scroll:

- Teach the young in the language of their dreams.

- Translate justice into the tongue of the people.

- Fund research in our own words, not just foreign ones.

- Give the drum back to the drummer.

Yet their children had been taught otherwise, that their tongues of many colors were not garments of wisdom, but rags of shame. Like the village boy who abandoned his father’s kente to chase foreign lace, they began to look down on the languages that first named the rains, the rivers, and the rituals.

In the courts, verdicts were now issued in foreign tongues, causing villagers to nod in fear, not understanding. In clinics, mothers heard diagnoses in terms that stole their peace. In classrooms, children failed not for lack of brilliance, but because their learning came in a language their soul had not met.

It was then that the elders invoked the memory of Ephraim Amu, the sage of Peki-Avetile, who wore fugu to lecture halls and sang truth in his mother tongue. He who told the nation that dignity is not imported. The voice of the drum is not inferior to the violin. A man who cannot pray in his grandmother’s language may say the words, but not reach the gods.

“He taught us,” said the Seer, “that to know thyself, you must first speak thyself.” Amu’s anthem was not only a song but a resistance. Against the erasure of the African tongue. Against the silencing of thought by borrowed grammar.

So the Council stirred the children once more to speak with pride. To let their voices ring with the cadence of home. To know that just as the kente’s strength lies not in one thread, but in the harmony of many, so too must their language tapestry be woven, with their own words at the center.

And thus they declared: “Let English walk beside us, not ahead of us. Let our tongues remember their roots, lest our thoughts forget their fruit.”

“Tete wƆ bi ka, tete wƆ bi kyerƐ“, The past has something to say and teach. Just as Ephraim Amu taught, our future will stand firmer when our words stand in our shoes.

And so it was said:

“When the mouth speaks what the heart remembers, wisdom returns to the village.”

For in Nunyãdume, they learned the final lesson, that a nation’s development is not merely in its buildings or budgets, but in the tongues that tell its story. “Let there be voice. Let there be mother-tongue instruction. Let there be laws translated for the people, healthcare delivered in trust, and governance conducted in the tongue of the governed.”

For a nation that forgets its language becomes a village of mute geniuses, wise, but unheard.”

Let the people of Nunyãdume rise.

Let them teach their children not just to speak, but to remember. They should teach that language was not just for exams, but for existence.

And as the first few verses in Genesis foretold, the Word came first and brought Light. And where there is Light, there is sight, growth, and direction.

Let Ghana speak again, not just in borrowed words, and in all its voices. Not for nostalgia, but for nationhood. Not for grammar, but for growth. Not for the past, but for the future.

Let us not be a nation with golden tongues sealed in forgotten chests.

Written by Dr. Eugene Dordoye, Ag. CE of MHA